Theoretical and Descriptive Analysis: BOP as a Monetary Phenomenon

A balance of payments (BOP) deficit or

surplus represents a transient stock adjustment process evoked by initial

inequality between actual; and desired money stock. The monetary approach

maintains that the BOP are essentially a monetary phenomenon and the root cause

in the payments imbalances are the disequilibrium between the demand for and

supply of money. This proposition is often called strong version of the

monetary approach.

As the Elasticity and Absorption approaches

fail to provide the correcting measures of balance of payments deficit in the

less developing countries; another approach is still available which is known

as the Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments. According to the monetary

approach, the balance of payments is purely a monetary phenomenon. Being a

monetary phenomenon, it can be corrected only through the monetary measures.

According to the monetary approach, the balance of payments is a monetary

phenomenon is related to inflow and outflow of international reserves. If money

supply is defined as the sum of reserve and net credit creation, the monetary

authority can hold a control over only a single component of it. That is only

net credit creation. So, the monetary authority can influence the money supply

just by controlling a component of the money supply and through it the

international reserve. So, viewed from the supply side of money, the balance of

payments problem is a monetary problem and monetary policy is applicable to

control it. The monetary approach relates a country’s overall international

surplus or deficit to change in the aggregate balance sheet of its monetary

institutions.

Unlike “elasticities” and “absorption”

approaches, the MABP treat BOP as monetary problems and should be tackled by

explicitly investigating the domestic monetary behaviour .The proponents of the

monetary approach contend that beside the monetary factors, real factors do

affect BOP through monetary channels. The central point of the monetary

approach to balance-of-payments policy theory is the balance-of- payments

deficits or surpluses reflect stock disequilibrium between money demand and

supply in the market for money.

From

Your Article Library: The monetary approach to the balance of

payments is an explanation of the overall balance of payments. It explains

changes in balance of payments in terms of the demand for and supply of money. According to this

approach, “a balance of payments deficit is always and everywhere a monetary

phenomenon.” Therefore, it can only be corrected by monetary measures.

The Theoretical Analysis:

Given these assumptions,

the monetary approach can be expressed in the form of the following

relationship between the demand for and supply of money:

The demand for money (MD)

is a stable function of income (Y), prices (P) and rate of interest (i)

MD=f(Y, P, i) …(1)

The money supply (Ms) is

a multiple of monetary base (m) which consists of domestic money (credit) (D)

and country’s foreign exchange reserves (R). Ignoring m for simplicity which is

a constant,

MS = D + R … (2)

Since in equilibrium the

demand for money equals the money supply,

MD = Ms .. (3)

or MD = D + R [MS = D +

R] …(4)

A balance of payments

deficit or surplus is represented by changes in the country’s foreign exchange

reserves. Thus

∆R = ∆MD – ∆D … (5)

Or ∆R = B … ( 6)

Where B represents

balance of payments which is equal to the difference between change in the

demand for money (∆MD) and change in domestic credit (∆D).

A balance of payments

deficit means a negative B which reduces R and the money supply. On the other

hand, a surplus means a positive B which increases R and the money supply. When

B = O, it means bop equilibrium or no disequilibrium of BOP.

The automatic adjustment

mechanism in the monetary approaches is explained under both the fixed and

flexible exchange rate systems.

Under the fixed exchange

rate system, assume that MD = MS so that BOP (or B) is zero. Now suppose the

monetary authority increases domestic money supply, with no change in the

demand for money. As a result, MS > MD and there is a BOP deficit.

People who have larger

cash balances increase their purchases to buy more foreign goods and

securities. This tends to raise their prices and increase imports of goods and

foreign assets. This leads to increase in expenditure on both current and

capital accounts in BOP, thereby creating a BOP deficit.

To maintain a fixed

exchange rate, the monetary authority will have to sell foreign exchange

reserves and buy domestic currency. Thus the outflow of foreign exchange

reserves means a fall in R and in domestic money supply. This process will

continue until MS = MD and there will again be BOP equilibrium.

On the other hand, if MS

< MD at the given exchange rate, there will be a BOP surplus. Consequently,

people acquire the domestic currency by selling goods and securities to

foreigners. They will also seek to acquire additional money balances by

restricting their expenditure relatively to their income.

The monetary authority on

its part, will buy excess foreign currency in exchange for domestic currency.

There will be inflow of foreign exchange reserves and increase in domestic

money supply. This process will continue until MS = MD and BOP equilibrium will

again be restored. Thus a BOP deficit or surplus is a temporary phenomenon and

is self-correcting (or automatic) in the long-run.

·

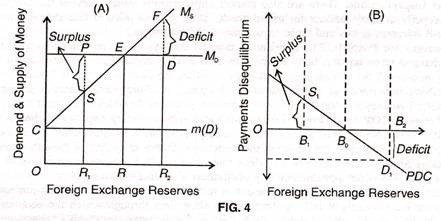

This is explained in Fig. 4 In Panel (A)

of the figure, MD is the stable money demand curve and MS is the money supply

curve. The horizontal line m (D) represents the monetary base which is a multiple

of domestic credit, D which is also constant. This is the domestic component of

money supply that is why the MS curve starts from point C.

·

MS and MD curves intersect at point E

where the country’s balance of payments is in equilibrium and its foreign

exchange reserves are OR. In Panel (B) of the figure, PDC is the payments

disequilibrium curve which is drawn as the vertical difference between Ms and

MD curves of Panel (A). As such, point B0 in Panel (B) corresponds to point E

in Panel (A) where there is no disequilibrium of balance of payments.

·

If MS < MD there is BOP surplus of SP

in Panel (A). It leads to the inflow of foreign exchange reserves which rise

from OR1 to OR and increase the money supply so as to bring BOP equilibrium at

point E. On the other hand, if MS > MD, there is deficit in BOP equal to DF.

·

There is outflow of foreign exchange

reserves which decline from OR2 to OR and reduce the money supply so as to

reestablish BOP equilibrium at point E. The same process is illustrated in

Panel (B) of the figure where BOP disequilibrium is self-correcting or

automatic when B1S1 surplus and B2D1 deficit are equal.

·

Under a system of flexible (or floating)

exchange rates, when B = O, there is no change in foreign exchange reserves

(R). But when there is a BOP deficit or surplus, changes in the demand for

money and exchange rate play a major role in the adjustment process without any

inflow or outflow of foreign exchange reserves.

·

Suppose the monetary authority increases

the money supply (MS > MD) and there is a BOP deficit. People having

additional cash balances buy more goods thereby raising prices of domestic and

imported goods. There is depreciation of the domestic currency and a rise in

the exchange rate.

·

The rise in prices, in turn, increases the

demand for money thereby bringing the equality of MD and MS without any outflow

of foreign exchange reserves. The opposite will happen when MD > MS, there

is fall in prices and appreciation of the domestic currency which automatically

eliminates the excess demand for money. The exchange rate falls until MD = MS

and BOP is in equilibrium without any inflow of foreign exchange reserves.

The Descriptive Analysis: How BOP as a purely monetary phenomenon?

The MABP approach

emphasizes the budget constraint imposed on the country's

international spending through which the excess of domestic flow demands over

domestic flow supplies, and of excess domestic flow supplies over domestic flow

demands, are cleared. Accordingly, surplus in trade account and capital account

respectively represent excess flow supplies of goods and securities, and a

surplus in the monetary account reflects an excess flow demand for money.

Consequently, in analyzing the money account, the rate of increase or decrease

in the country's international reserves, the monetary approach focuses on the

determinants of the excess flow demand for or supply of money. A consistent use

of budget constraint implies that the monetary approach recommends an analysis

in terms of the behavioral relationships directly relevant to the money

account, rather than an analysis in terms of the behavioral relationships

directly relevant to the other account and only indirectly to the money account

via budget constraint.

A deficit

in terms of an excess of aggregate payments over receipts has two important

aspects, its monetary implication, and its relation with the aggregate activity

of the economy. This implies one of two alternatives. The first is that the

cash balances of residents are running down, as domestic money is transferred

to the foreign exchange authority. Eventually, cash balance would approach the

minimum that the community wished to hold and in the process the disequilibrium

would cure itself, through the mechanism of rising interest rate, tighter

credit creations, reduction of aggregate expenditure, and possibly an increase

in aggregate receipts. In this case where the deficit if financed by

dishoarding; it would be self-correcting in time, but the economic policy

authorities unable to allow the self-correcting process run its course, since

the international reserves of the country may be a small fraction of the money

supply that would be exhausted well before the running down of money balance

had any significant corrective effect.

The second is that the cash balance of residents are filled again by

open market purchases of securities by the monetary or foreign exchange

authority, as would happen automatically if the monetary authority followed a

policy of pegged interest rate or the exchange authority automatically re-lent

to residents any domestic currency received from residents or foreigners in

return for sales of foreign exchange. In this case, the money supply in

domestic circulation is maintained by credit creation, so that the excess of

payments over receipts by the residents could continue indefinitely without

generating any corrective process, until reserves exhaustion force the economic

policy authorities to change their policy in some respect.

Hence,

the balance of payments deficit implies either dishoarding by residents,

increase in velocity of circulation, or credit creation by the monetary

authority to maintain money supply. Similarly, the balance of payments surplus

necessarily involves either an increase in hoarding by domestic residents or a

decline in domestic credit created by the central bank. Since a deficit

associated with increasing velocity of circulation will tend to be

self-correcting, a continuing balance of payments deficit ultimately requires

credit creation to keep it going. Therefore, we consider balance of payments

deficit as being essentially monetary phenomenon under either of two cases: too

low a ratio of the international reserve relative to the domestic money supply,

so that the economic policy authorities cannot rely on the natural

self-correcting process, or follow of governmental policies which oblige the

authorities to feed the deficit by credit creation.

The

difference between Keynesian and monetary models of the open economy is that

the Keynesian assumes that the central bank can sterilize the effect of the

balance of payments on the money stock, while Monetarists are models in which

sterilization does not occur. This is because sterilization involves motivating

(rising or falling interest rate) wealth holders to alter continuously their

portfolio balance between money and bonds. This in turn reinforces surplus or

deficit on balance of payments through capital flow and outflow. The important

conclusion is that a country which operates a fixed exchange rate or managed

float cannot have an exogenously determined money supply unless it can be

sterilized successfully.

The

money supply cannot be controlled by the monetary authorities because it is

affected by the balance of payments, which in turn depends on decision of the

private sector, given the exchange rate the monetary authorities decide to

maintain. If foreign currency flows cannot be sterilized, then the government

cannot choose both the exchange rate and the money supply targets. If the

government chooses a particular exchange rate, then the money supply has to

adjust to be consistent with it.

Under

flexible exchange rate the balance of payments remain at zero because the exchange

rate adjusts to achieve overall balance of payments equilibrium. The domestic

money supply therefore is exogenous because the base money is exogenous in the

same way as in closed economy. The government can now select the stock of money

as a policy target, but has to accept whatever the rate of exchange that is

consistent with money supply target.

If

the exchange rate is managed then the resulting imbalance of the balance of

payments affects it so that the domestic money supply is endogenous.

Anti-monetarists

argue that the money supply is not exogenous under any circumstances because

the multiplier (m) varies substantially and erratically and because the base

money is not under monetary authorities control. Instead they have to vary the

base money in response to the private sectors' demand for credit and money,

hence the money supply always adjusts to whatever the demand for it.

Given

this difficultly of sterilizing a persistent surplus or deficit over an

extended time period, the monetary approach to the theory of the balance of

payments adjustment mechanism is along run phenomenon. Musa (1976) noted this

phenomenon by stating that the feature of the monetary approach is a

concentration on the long run consequences of monetary policy and parametric

changes for the behavior of the balance of payments coupled with an eclectic

view of the processes through which these long run consequences come about.

Mundell (1960) demonstrated that monetary policy is a more effective than

fiscal policy, in attaining external balance, because monetary policy improves

both the current and capital accounts of the balance of payments.

Under

fixed exchange rate an expansionary monetary policy must always leads to a

deterioration in the BOF, while a contractionary monetary policy will always

lead to an improvement in the Balance of Finance (BOF). When monetary policy

starts from an equilibrium position with BOF zero, its effects are nullified in

the long run under a fixed exchange rate. Here the money stock must be largely

endogenous. This conclusion also holds for an open economy model with perfect

capital mobility. If monetary expansion occurs when the BOF is in surplus, then

this would speed up the increase in the money stock that would have eventually

occurred as a result of a surplus. The surplus will diminish and there will be

smaller accumulation of foreign reserves as a result of monetary expansion.

Here the effect of the policy on the domestic money stock will not be

nullified. Similarly, when the BOF is in deficit under a fixed exchange rate, a

monetary contraction will accelerate the adjustment in the domestic money stock

that would eventually occurred as a result of foreign exchange reserve losses.

This will limit the extent of reserve loss and in this case the money

contraction is not nullified in the long run.

Thus the monetary approach views the BOP as a purely monetary

phenomenon, with money play a fundamental role in its determination.

Comments